Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Annie Dillard's Pulitzer-Prize winning book published 50 years ago this year, draws you in. You should read it. And so should I.

And so I am. Few people are aware like Annie, few people have her imagination, and precious few can write like she does. When I read Pilgrim I decide my best prose is ham-fisted and my imagination dull. But I keep working at it, which is what she would likely advise.

This week in the chapter titled simply “Flood,” I read about a flood that struck Tinker Creek in 1972. She speaks in particular of the flooding around the bridge where Ardmore Road crosses the creek. If you know the neighborhood you know that bridge: it is a half mile or so southeast of Hollins University, one of two small bridges in that neighborhood before Tinker makes its way further along and crosses under Hollins road.

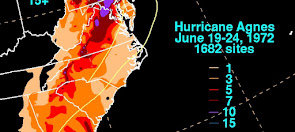

In the telling Annie even mentions various families: the Bings, Atkins, and Bowerys. The flood, says Annie, was a result of Hurricane Agnes which wreaked havoc along the eastern seaboard and far inland in June/July of that year. Roanoke received well over 10” of rain from Agnes and Tinker Creek swelled far beyond its banks. Indeed, the water was over the bridge as much as two feet, a good 10-12 feet above normal.

Annie is in full form seeing the flood. “The water is so deep and wide it seems as though you could navigate the Queen Mary in it.” “The floodwater roils to a violent froth...there are dolls, split-wood and kindling...whole bushes and trees, rakes and garden gloves. Wooden, rough-hewn railroad ties charge by faster than any express...I expect to see anything at all...Why not a cello, a basket of breadfruit, a casket of antique coins?”

It's mid-day and neighbor men are returning early from work to help where they can. There's not much to do though a truck comes to pump out the Bowery's basement. The other bridge, over on Clearwater Ave., looks to be in trouble with a large tree wedged against it. Road crews try to remove it to no avail. The Bings' house lower floor is flooded floor to ceiling. Neighbors come together on the Ardmore bridge, then gather at the Bings'; children play safely in adjoining yards, and all wait to see when the water will recede.

What does one say about floods but to stay clear if you would live? If you fell in, “You couldn't live. Mark Spitz couldn't live. And if they ever found you, your gut would be solid red clay.”

I've seen my share of floods. More than once the North Fork of the Kentucky River blocked our rural home's access to the highway. In the Great Flood of 1993 I crossed the spillway bridge of Tuttle Creek Reservoir before they closed it and saw the thundering waters claw out the hillside on their way to the sea. And in the western Kansas of my boyhood the rare flood found me wading knee-deep in drain channels or daring death in wannabe swimming holes gorged by the heavy rain.

I loved the flood somehow, and so did Annie. Her telling is simple and homey, families and neighbors, fear and trouble and wonder: even beauty in the terror. One comes away feeling the lead-up: hot muggy day, animals acting funny, plenty of rain but no real warning. And then it came and all was different, unpredictable, vulnerable. Few things speak reality like nature, and floods do it convincingly.There's little to add to Annie's account, much like one can't add to a flood. It is all there is and it demands your attention. Ignore it and get swept away.

It leaves me, like all of the book, seeing better and feeling the beauty of life in all of its expressions. All of life is of a fabric – even something as mundane, natural, and scary as a flood. Annie's neighborhood stood by while the flood ran its course. The next day they kept putting the pieces back together, remembered the adventure, and hoped the floodwaters would stay away for many more years.

And over 50 years later we talk about it, wonder about the people and their memories, and can't escape a simple sense of the grace of life that, unlike the flood waters of Agnes, never fully abates.

No comments:

Post a Comment